the Mind’s gaining that prophetic sense / Of future change, that point of vision. Wordsworth, for his part in “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways,” describes “. . . In fact Crane is arguing that machines must lose their “glamour” so that they appear in their “true subsidiary order in human life as use and continual poetic allusion subdue novelty.” Both Wordsworth and Crane share notions about how language becomes imbued or endowed with human associations and how experience is “converted,” in Crane’s words, by the “spontaneity and gusto” of the poet.

#Tremulous twinkle full#

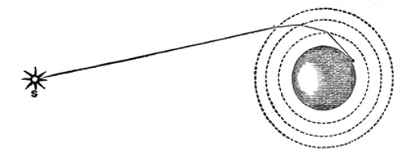

In his brief 1930 essay, “Modern Poetry,” he writes, “For unless poetry can absorb the machine, i.e., acclimatize it as naturally and casually as trees, cattle, galleons, castles and all other human associations of the past, then poetry has failed of its full contemporary function.” I don’t mean to suggest that no progress was made by poets grappling with the proliferation of man-made things between 18. This crowding in of the thingness and man-made particularity of the contemporary world is rare in the Romantic poets, who were apt to subscribe to John Baillie’s notion of the sublime in which “Vast objects occasion vast Sensations.” Nevertheless, in Wordsworth, more than in Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, and Byron, we can see it beginning to encroach, for example in “Book VII of the Prelude: London Residency” and, another sonnet, “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802.” Wordsworth’s recognition of these things is grudging and one feels his conviction is powered more by an argument that attempts to extend the range of the sublime-an aesthetic notion-rather than by a deeply held belief.Īlmost exactly a century later, Hart Crane can talk rather easily about the “Machine Age,” but like Wordsworth, he still needs to make a case for the worthiness of the machine as a poetic emblem.

Steamboat, viaduct, and railway are all words that came into use during Wordsworth’s lifetime. Of hope, and smiles on you with cheer sublime.Īlthough it is interesting to see how willingly Wordsworth makes art of metal and steel-the interchangeable part rushing to meet the assembly line-what is as equally interesting to me is the way the diction of the title stands in stark contrast to the diction of the poem itself. Pleased with your triumphs o’er his brother Space,Īccepts from your bold hands the proffered crown Her lawful offspring in Man’s art and Time, In your harsh features, Nature doth embrace Of future change, that point of vision, whence To the Mind’s gaining that prophetic sense Nor shall your presence, howsoe’er it mar Shall ye, by Poets even, be judged amiss! Motions and Means, on land and sea at war whence / May be discovered what in soul ye are.” Regardless of how “harsh” these features are, Wordsworth concedes that they should be embraced by “Nature” because they are products of “Man’s art.” In Wordsworth’s 1833 sonnet, “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways,” the poet of recollection and tranquility is forced to look into the future by these conveyances and conveyors, these “Motions and Means,” to consider how they might “mar / The loveliness of Nature” and “prove a bar / To the Mind’s gaining that prophetic sense / Of future change.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)